Thoughts about…

Reflection on My Tahoe Big Year

I realize that it’s a bit premature to be reflecting on this year’s Tahoe Big Year (TBY) when it’s only October. However, I have the time to write something longer and more reflective right now since I’m in-between seasonal work. And, you know me, once the snow starts to fly I’ll be talking non-stop about cross-country skiing! And, honestly, this has been a big deal for me. I’ve sacrificed a lot this year in an effort to document 211 birds (to-date), so I don’t just want it to be an afterthought come December.

Besides, finding at least 200 bird species rather than placing anywhere in particular in the rankings has always been my goal. Where I end up on the Leaderbird in relation to everyone else on December 31st really doesn’t matter. Therefore, this feels appropriate since I’ve technically already achieved my goal.

All of that said, I’m clearly going to be talking about birds at Lake Tahoe. So if that’s not your thing, I totally understand if you tune out and just look at my photos. Keep in mind, though, that I’m really just talking about my experience working toward a 12-month goal. The details might be specific, but the approach is universal. So leave if you must, but I encourage you to stick around if you have the time.

Okay, here we go…

In 2021, I was the third and final person to log 200 birds out of approximately 100 participants. That occurred on December 7th when I saw, with some fellow TBYers, a Long-tailed Duck in one of the heated ponds at Edgewood Golf Course. I then logged my 201st bird, a pair of Barrow’s Goldeneyes, at Donner Lake on December 17th. So I finished that year’s TBY with a total of 201 birds. For reference, those two birds are listed as being casual and rare, respectively (I’ll talk about classifications later). Basically, though, there was no guarantee that I was ever going to find either of them. And I actually tried upwards of a dozen times to find a Barrow’s Goldeneye earlier that spring. So I could’ve easily just finished with 199 birds which, obviously, would’ve been very disappointing.

Needless to say, I didn’t want to repeat that experience this time around. Eking out those last few birds of the year was stressful. That’s because once the fall migration comes to a close, generally speaking, what’s here is here and what’s gone is gone. You’ll be hard-pressed to find many, if any, new birds by the time December rolls around. That’s not to say that you can’t find rare stuff, because I just illustrated that it’s possible. And I do have many birding friends who have also found really great stuff in December. But most of those birds are hard-to-find species, so you don’t really want to count on finding anything new at that point in the year.

Another note about bird migration at Lake Tahoe is that not everything that flies through in the spring returns in the fall. I haven’t been studying long enough to know the reasons for this behavior, other than weather patterns obviously dictate what flies when and where. I just know this through my own observations, as well as talking to long-time local birders and experts. This is why it’s just best to find as many birds as possible in the spring, which is what I did this year (compared to my approach in 2021).

I was the second person to find 200 birds this time around and, surprisingly, I did so on August 26th. I was way ahead of my own expectations, but that was just fine with me! Currently, there are five other TBYers who’ve also accomplished the feat out of roughly 75 people. And there are a few more within striking distance of 200.

I obviously can’t speak for everyone else, but I’m pretty sure that those of us who have reached 200 so far this year made it a point to do so sooner rather than later. I don’t believe any of us have wanted to deal with the late-season desperation that rears its ugly head in October, November, and December. So, basically, many of us have been grinding ever since January 1st to make 200 happen.

Historically, there’ve been roughly 320 bird species documented in the Tahoe/Truckee region. So 200 birds is about 62% of that total number which seems easy enough to reach, right? We’re talking “D” work, here, if we were in a classroom!

Maybe so, but life isn’t exactly like the controlled environment of a classroom.

In 2016, the Tahoe Institute for Natural Science (TINS) published its Birds of Lake Tahoe Basin seasonal checklist. In it, they listed the 312 bird species that had been documented in the Tahoe region up to that point. The checklist includes the common and scientific names of those birds, and classifies them as being either Common, Uncommon, Rare, or Casual for each of the four seasons.

This year alone, however, has yielded first sightings of a Vermillion Flycatcher thanks to Jenny Scott and Jeff Miller and a Thick-billed Longspur by Chris Siano. Additionally, an expert who was performing a “point count” in South Lake Tahoe this summer discovered a Veery, which is a Thrush normally found on the east coast. During the 2021 TBY, Jenny Sweatt had a first sighting for the Tahoe Basin of a Northern Waterthrush, and Scott Dietrich (RIP) logged a first sighting of a Nelson’s Sparrow. In the non-TBY years of 2020 and 2023, respectively, I’m on record for having first Tahoe sightings of a Summer Tanager and a Yellow-throated Vireo. I’m sure there have been other first sightings that I’m unaware of, so the fact that random stuff pops up around Lake Tahoe once or twice a year just means that the checklist is probably due for an update. Regardless, 320 birds is a good enough number by which to use for reference.

Now, a large percentage of those 320 birds are listed as either being “rare” or “casual” to the Lake Tahoe region. Rare is defined as being “expected annually, or nearly so, but always in small numbers.” And casual birds are even harder to find as there are “very few records of this species to date.” Essentially, all of those previously mentioned first sightings would be classified as casual since there’s no real rhyme or reason for their arrival. They may re-visit Tahoe in five years from now or, perhaps, they’ll never be seen again. There’s just no telling.

So what is the actual number of birds listed in the Lake Tahoe Basin checklist that are considered to be strictly rare and/or casual?

That number is about 135!

Therefore, there are only about 185 common and uncommon bird species in the Tahoe region. That means that in addition to finding every one of those birds, for example, you’d need to find at least 15 rare and casual ones in order to reach 200.

But just because a bird is listed as being common or uncommon doesn’t mean that it’s a guaranteed find. For example, the American Goshawk, Northern Pygmy-Owl, and Northern Saw-whet Owl are notoriously difficult to find despite all of them being classified as uncommon, year-round at Lake Tahoe. So, essentially, you can’t assume that you’re going to find all 185 common and uncommon birds for your TBY.

But weird stuff can and does happen in the bird world.

For example, an American Goshawk actually did visit Jenny and Bob Sweatt’s backyard multiple times during the spring. It was bizarre because Goshawks are super elusive and are considered to be forest hunters. But Jenny and Bob live in a waterfront community on Lake Tahoe. The fact that the Goshawk showed up as often as it did is the only reason myself and many other TBYers even saw one this year. In fact, I’ve only seen a Goshawk twice before this year. Granted, I haven’t been birding for all 19 years that I’ve been living in Tahoe but trust me when I say that they’re not easy to find.

Some other examples of the unpredictable nature of birding include the Western Cattle Egret that Meghan Walsh and Emily Frey found in the spring. That Egret is extremely rare for Tahoe with less than a few observations of it in the region on record. However, it stuck around for at least a couple of days. So many of us were able to find it with relative ease. The same goes for the Lark Bunting that Geoff Hanlon discovered in late summer. Another really rare bird for Tahoe, but it spent at least two days in the same easily accessible location.

At the other end of the spectrum, however, is that first sighting of the Thick-billed Longspur that I previously mentioned. Based on the fact that no one was able to re-acquire it, and people did hustle to find it, we assumed that it didn’t stick around for longer than hour or two. There’s a host of other rare and casual birds that came and went in a similar fashion this year, such as a Parasitic Jaeger found by Michael Myers and a Common Tern by Katherine Roberts. Neither of which have been found again so, inevitably, we all leave a few birds on the table with each TBY. Whether it’s a minute or a day, if the bird is gone it’s gone.

This is why the only thing that you can really depend on and plan for when trying to find 200 birds for your Tahoe Big Year is that you’re going to be doing a lot of hard work! You have to make searching for birds a daily habit. In other words, you have to grind every day.

But trying to find 200 birds out of a possible 320 is purely theoretical. There’s no chance in hell that all 320 documented birds will ever be at Lake Tahoe in the same year. Never. So let’s look at this endeavor from a perspective based more in reality.

That reality is that there have only been 225 bird species observed so far during this year’s Tahoe Big Year.

Essentially, we eliminated 95 birds right off the top of that list of 320 this year. You know, just to make things interesting! So 62% is one thing, but now you have to find 89% of what’s actually here.

This is all sounding more and more ludicrous, isn’t it?

Also keep in mind that of those 225 birds, five or six of them (currently) have only been observed by a single person. And there are four or five more records of rare birds being found by a small handful of people. In those cases, the people were either birding together when they saw it or heeded the alert within less than 30 minutes, for example, and re-acquired the same bird. Or another individual randomly observed the rare bird in question on their own at a different time and in a completely different location.

An example of that last scenario is the rare (for Tahoe) Ferruginous Hawk that I saw at Carson Pass on October 12th. I only saw it for about 15 seconds as it flew toward me and then over a ridge to the west, never to be seen again. Fortunately, I got plenty of photos for ID confirmation because no one would’ve believed me due to its rarity. However, a week later, Will Richardson observed another Ferruginous Hawk flying over Martis Valley. This location is on the exact opposite side of Tahoe and, in fact, outside of the actual watershed. I haven’t heard of anyone else seeing that hawk despite Will sending out an alert. And people did give it a try.

Having two different sightings of the same species of rare bird in different locations is great because it provides hope. Could there be more? Of course. But you can’t plan to find something like that because those sightings are so random and transient. Literally, both hawks were passing through the area during their fall migration. So unless you planted yourself at either location for days on end, your odds of seeing that particular bird just aren’t that great. Rare birds are rare for a reason, after all.

Playing it conservatively, we could easily eliminate another 10 species from that list of potential birds. This is because those random sightings most likely represent a one-and-done type of scenario like I just illustrated. Again, a minute or a day, if it’s gone it’s gone.

So instead of having 320 potential candidates this year, that number of options is much closer to 215. And this yields a 93% observation rate. That sounds even crazier, right?

Well, it is! And that’s why so few people end up logging 200+ birds for their Tahoe Big Year.

For comparison, we collectively found about 240 species during the 2021 TBY. And that was a pretty big year. Amazingly, Jenny Sweatt led the pack by finding 233 of those birds! Now that’s what I call grinding.

Could we, as a group, find 15 more species before this year is over? It’s entirely possible. However, it’s been hit and miss for the past few weeks so the probability of doing so decreases with every passing day. And everything that’s still on the table for these next two months is considered rare and casual for Tahoe. I don’t want to sound like a naysayer, but I think it’s going to be difficult to find more than 5-10 new bird species, let along 15.

Regardless of how you crunch the numbers, though, the chances are that on any given Tahoe Big Year the final tally will most likely yield 240 or less bird species. So that means you’re going to need to find closer to 83% of what everyone else has located for the year in order to reach 200 birds.

Again, I realize that we still have two months and some change left of the year so it’s totally possible that we’ll find a bunch of new birds. But I just don’t think we’re going to beat 2021’s number. There were a few key factors at play that year, compared to 2024, that seemed to bolster the numbers.

The first is that there were roughly 25 more participants in 2021. The more you look the more find, after all, and 25 more sets of eyes represents a lot of looking potential.

Of those 25 people, I’m including a community friend that has since passed away due to a long bout with cancer. His name was Scott Dietrich and he was a birding expert who, literally, lived out of his car for much of 2021 so that he could spend time birding around Lake Tahoe. He technically wasn’t participating in the TBY, but he was providing us with updates based on his observations.

I actually only met him for the first time on September 12th, 2021, when I visited Lake Forest Beach to find the Nelson’s Sparrow that he discovered the previous day. This was the day after I returned to Tahoe from being evacuated for 11 days due to the Caldor Fire. I quickly discovered just how kind and generous Scott was, and I’m grateful for the opportunities that I had to spend time with him. He was super knowledgeable, and he was really fun to be around. I’m also grateful for his bird expertise because he helped me to reach 201 species that year. For example, with him I saw that Nelson’s Sparrow, as well as a Vaux’s Swift, Hammond’s Flycatcher, Black Scoter, and a White-winged Scoter (both Scoters on the same day, no less!).

Although he was known by many people for many years in the Tahoe birding community, I don’t know that anyone knew that he had been battling cancer for as long as he had. And I definitely don’t think anyone knew just how serious it was, except for maybe himself. He died about a year later, and it was a shock to all of us.

He is missed.

In addition to there being significantly less participants this year, a number of our local birders have been taking time off to travel the world and visit family. And leaving the Tahoe Basin is generally considered “verboten” during Tahoe Big Years! I joke but it’s definitely a reason that we’re not finding as much because, again, there just aren’t as many eyes out and about searching for new birds.

Another contributing factor to this year’s smaller bird count (at least so far) is that, despite a less than stellar preceding winter, there’s water everywhere. This may sound counterintuitive, but it’s actually the shoreline (aka mud) that attracts shorebirds rather than the water itself. Sandy beaches are great for people, but they don’t usually host the necessary organisms on which shorebirds like to feed. Personally, I have yet to see a Short-billed Dowitcher, Wilson’s Phalarope, Semipalmated Plover, Sanderling, or Dunlin (all of which I saw in 2021). Other TBYers saw the first two on that list, but there were very few of either of them to find. And they didn’t stick around for very long.

In contrast, due to the low water level back in 2021, we could walk hundreds of meters into the lake at locations such as Lake Forest Beach (near Tahoe City) and the Upper Truckee Marsh (in South Lake Tahoe). Also, we could actually walk from the Upper Truckee Marsh side of the Upper Truckee River (as it enters Lake Tahoe) to the Cove East side of the shore by the time October rolled around. That is definitely not happening this year.

Earlier in the season, I believed that there was a general lack of volume of birds. We were seeing a variety, but there just didn’t seem to be many of any given species. And, honestly, it felt like for the first six months we were all chasing the same exact birds. I actually got quite annoyed with this experience which is why I removed myself from the group birding text earlier in the spring. I wanted to find my own birds. I do realize that this’ll always be the case when it comes to rare stuff. That is, we’ll be chasing the same bird. However, it also began to feel like that with the more common species.

Now that time has passed, however, my belief in scarcity boils down to perception. There’s no question that there has been a lack of shorebirds. But most of the other stuff now seems to be on par with previous years.

The first reason for that perception of scarcity was the fact that there were so many of us searching so early and often. As a result, we found many out-of-season species and birds at the leading edge of their migratory patterns. So there probably was, in fact, a general lack in volume during those first few months because, again, we were all grinding so hard so early. In other words, we hadn’t given many of those birds enough time to get to Tahoe! It was simply too early in the season for the main flock to be here.

The second reason for my belief that there was a lack in volume has to do with “baseline.” What happens during a big year is that once you find a species, you tend to tune it out moving forward. That way you can continue to find new stuff without getting bogged down by old business. Once you find something, it often gets re-categorized as baseline. In other words, it becomes wallpaper. No need to look any closer because we’ve already checked that box. Therefore, I probably just tuned out a lot of birds because I found them earlier in the year.

In fact, now that summer has come and gone and we’re deep into the fall I’ve had multiple observations of species that I’d normally consider to be hard to find. For example, I had never seen a Black-throated Gray Warbler prior to this year. But I’ve now seen them on five separate occasions. I usually only observe Cedar Waxwings once or twice a year, but this fall I’ve seen hundreds of them. I seldom see Lincoln’s and Golden-crowned Sparrows, but I’ve been fortunate to have had many encounters with each of them thus far. And I’ve rarely seen Merlins and Golden Eagles over the years. But this year I’ve seen them six and three times, respectively.

Additionally, I’ve seen many lifer birds this year. Those include the Thayer’s/Iceland Gull (1/5), Western Cattle Egret (4/2), Red-naped Sapsucker (4/5), Franklin’s Gull (4/25), Vermillion Flycatcher (4/26), Black Tern (4/27), Yellow-billed Loon (5/2), Lark Sparrow (5/8), Bullock’s Oriole (5/12), Sage Thrasher (5/14), Swainson’s Thrush (6/15), Tricolored Blackbird (7/14), Western Flycatcher (8/1), Black-throated Gray Warbler (8/27), Lark Bunting (9/6), Sabine’s Gull (10/1), Purple Finch (10/5), Ferruginous Hawk (10/12), and American Goldfinch (10/15).

To prove that I wasn’t always just chasing everyone else’s birds, I did manage to log a few first sightings for the year of some really great birds. In those cases, everyone else got to chase my birds 😉 They include the Red-necked Grebe (1/21), Gray-crowned Rosy-Finch (4/9, with Lynn Harriman), Golden Eagle (4/14), Franklin’s Gull (4/25, with Geoff Hanlon), Yellow-billed Loon (5/2, with Geoff Hanlon), Lark Sparrow (5/8), Bullock’s Oriole (5/12), Mountain Quail (5/18), Sabine’s Gull (10/1, with Heather Gaburo), and that Ferruginous Hawk (10/12).

My 100th bird of the year was a Black Phoebe and my 200th was a Common Yellowthroat.

A sub-goal for my Tahoe Big Year was to photograph every bird that I saw. This doesn’t necessarily mean that I had to get a print-worthy image of everything because that’s not a realistic goal. Seeing and identifying a bird is one thing, but capturing an ideal image of it is a whole other matter. I did want to get diagnostic shots of each bird, though, so that I could log them on iNaturalist. I like to document my nature observations through photos to aid in research via iNaturalist, for future reference for myself, and to keep myself honest. Basically, I use photos for ID confirmation and proof that I actually did see that Red-necked Grebe, for example.

The kicker, here, is that I’m one bird shy of getting photos of everything I’ve seen so far this year. And that bird is the American Goshawk, which is not an easy bird to find let alone photograph. So that’s still on my plate. I have hope, though, because nearly all year I’ve been trying to find and photograph a Greater White-fronted Goose. That’s because I technically saw one on February 3rd but it was with my binoculars, not my camera. So I never actually got a photo of it. That is, until this past Friday when I saw another and did manage to take some nice in-flight shots of it. But I still need photos of a Goshawk!

I’m grateful to all of my friends, mentors, and allies who’ve helped and supported me during this year-long project. I think this would be a near-impossible goal to accomplish if I was working completely independent and during a non-TBY year, for example. That’s because the community of TBYers are pretty much always out looking for birds. When we find something of note, we share that information through one channel or another so that others may be able to go and find it for themselves. And, trust me, this type of communication is essential to finding 200+ birds at Lake Tahoe.

I haven’t really throttled back since reaching 200. The pressure may be off, but there are still some great birds that will swing by Tahoe before the New Year. So I want to find and photograph them! Besides, this is my fourth Tahoe Big Year (2 plant/wildflower, 2 birds) in the past six years, and it’s going to be my last that I participate in earnest. It’d be so nice just to stop now, but that’s not really who I am or what I’m about.

So I’m going to keep on grinding until the very end 🙂

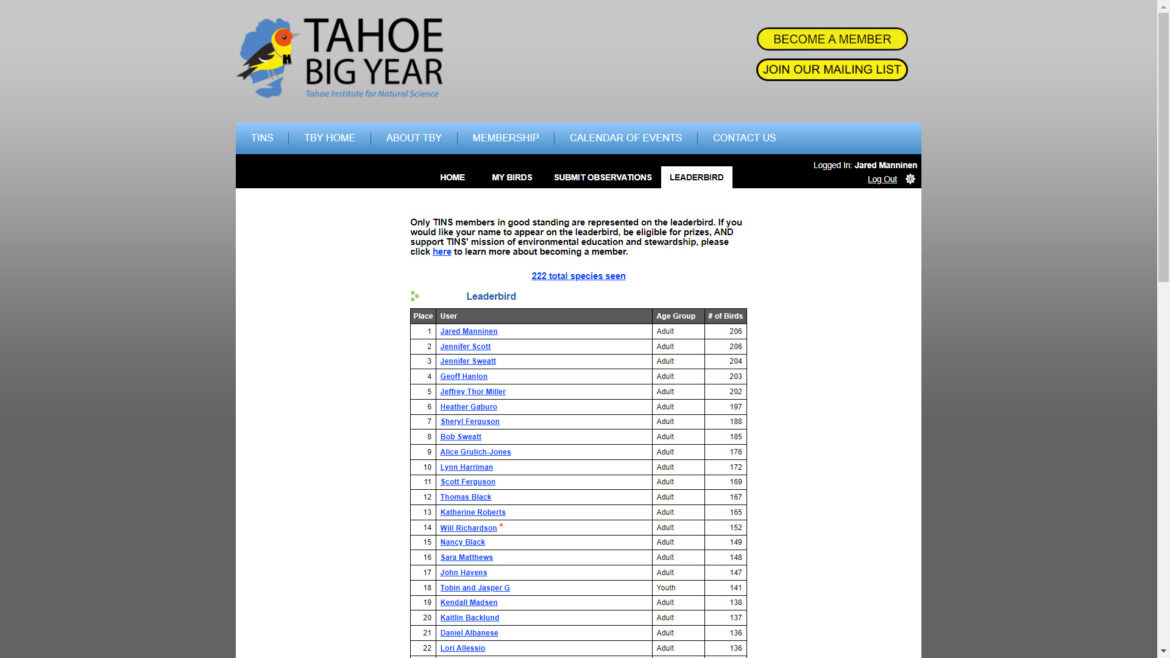

The current Tahoe Big Year standings are different than the screenshot below. So visit the official TBY website to see the current top 5 contenders.

Thanks for being a part of my life. Until next time…

-Jared Manninen

Tahoe Trail Guide is an online resource for hiking, backpacking, cross-country skiing, and snowshoeing in the Lake Tahoe region. In addition to trail data, I offer backcountry “how-to” articles and information about the local and natural history of Tahoe. Tahoe Swag is a collection of art and design products I create based on my love of the outdoors and appreciation for Lake Tahoe and the surrounding Sierra Nevada Mountains.

If you like any of the images I post in these newsletters, please contact me. I’d be more than happy to upload them to my RedBubble account so that you can order prints and other merchandise featuring the images.

A Note about Patreon and PayPal…

Patreon is an online platform for providing financial support to creators who provide quality digital content that’s otherwise free. I offer various subscription tiers starting at $3. And all subscription tiers from $6 and up will receive original artwork after six consecutive months of contributions. The button directly below the Patreon button is a way in which to provide a one-time payment via PayPal (if subscriptions aren’t your thing).

My newsletters here on JaredManninen.com, the articles that I publish on Tahoe Trail Guide, and the videos I upload to YouTube will always be free. But if you’re interested in contributing to the health and longevity of my websites and YouTube channel, consider subscribing. Even a little goes a long way 🙂

Comments (10)

Love your videos of skiing and birding! I just bought some skis for my wife and myself and have been watching your videos….. love yours by far the best on utube!

We are avid birdwatchers also.

I bought some very expensive Swarovski range finder binoculars and love them.

But my son and I have just got some Sigsauer 14×50 stabilizing binoculars….. they are a game changer!!!!

Just like having powerful glass on a tripod!

If you get a chance to look through them, you’ll see what I mean!

Keep up the great videos!

Rob Murphy

Klamath Lake, Oregon

Hey Rob!

Thanks for the kind words. I really appreciate it 🙂

That’s great that you have so many common interests within your immediate family. I imagine it’s quite rewarding to be outside with each other and sharing such cool experiences 🙂

I had to look up those Sig Sauer binos. Wow! They look pretty darned amazing. Although, maybe a bit out of my price range at the moment – haha 🙂 But if that’s what you have to work with, what else would you even need? I’m not a fan of tripods and scopes since they’re cumbersome when scrambling around. And then you can’t really take a photo (unless you do the hold-the-phone-up-to-the-eyepiece trick, which is always a challenge). So I like the portability of binos. I carry a set of binos and a DSLR camera, so I can toggle between the two. But with your binos (and it looks like they make a 18x, as well), that would be a dream combo. A lot of times I find myself taking photos of things in the distance so that I can zoom in on the picture to see what the bird/animal was. The stronger and cleaner imagery from your binos would definitely eliminate a lot of that extra work (i.e. deleting a bunch of crummy photos 🙂 ).

Anyway, thanks again for the nice feedback. And let me know if you ever have any questions (about xc skiing or birding, for that matter)!

I really enjoyed reading these musings, Jared, and especially glad to know that you’re hanging in there and getting a lot out of it! I feel bad that I wasn’t do any bird surveys this year, as that usually puts me on reliable goshawk territories I could point you to. I’ll definitely let you know if I come across any!! Keep hope alive; I’ve had that species hunting Mallards in the Upper Truckee Marsh, seen them on Christmas Bird Count near Baldwin Beach … they can still turn up just about anywhere!

Thanks for the kind words, Will. I appreciate it 🙂

Yes, these big years have been super educational and fun (in spite of them being so exhausting – haha!).

Big Year or not, I still want to get some nice photos of Goshawks so feel free to pass along any info about ones that you come across. I suspect it’s just a matter of time, but any help would be great 🙂

Thanks for all that you do! TINS is a great operation, and I’m glad I can be a part of some of the programs 🙂

Thanks, Jared! ……….You seem to really enjoy your work, and living location. Let know if you spot a Chinese Ring Neck pheasant. They seem to have abandoned Minnesota……I enjoy hunting them if I can find one. That seems to be getting harder & harder….Take of yourself. Wrestling season is just around the corner………..Gary Rettke

Thanks for the nice feedback, coach 🙂

I’ll keep my eye out for one of those pheasants, but I wouldn’t hold my breath. haha!

Good luck with the upcoming wrestling season, and you take care of yourself too!

FUN!!! Goshawk!! excellent!

I’ve joined local hawk-watchers occasionally here in Sonoma County for the migration counts and learned to recognize Ferruginous hawks. They migrate through in good numbers on the coast here, but don’t stay.

I was just looking this morning at the mini-framed-painting you sent, with the cards, as your thank you for my mini-Patreon-sponsor contributions. Thank you! A touch of the mountains!!

Hey Mary!

Glad you like the artwork. Those little mini-paintings seemed to be a hit at my job this summer 🙂

That sounds like a cool project to be a part of. I’ve helped out in the past on the Tahoe Christmas Bird Count and Mid-winter Bald Eagle Count. Hopefully I’ll be able to do that again this coming winter. I wish I saw more Ferruginous Hawks. I hear they like to winter in the Carson Valley, so I may make some trips down there in January/February to see if I can get some better photos.

Thanks again for all of your support! I totally appreciate it 🙂

A lovely write up Jared! Bird on, for a few more months 😀

Thanks for the words of encouragement! I sure will keep birding 😉